When I was a child and things got hectic at home, I found sanctuary in the pages of a book (mostly British fantasy novels). The characters in those books never looked like me or lived a life like mine, but that was part of the appeal; books were mostly a way to escape my own reality, and over the years I became convinced that I needed to become a different person and live someplace else in order to be truly happy. As a young woman I acted on that belief and left Canada for a "new and improved" life in the US.

Writing and teaching for 20 years in this country has taught me a lot about the fine line between fantasy and reality when it comes to matters of race, and this past summer has been a particular education. I had hoped to finish the final novel in my "freaks & geeks" trilogy, and spent a week in Dakar, Senegal conducting research. But when I got back to Brooklyn, events in the news left me at a loss for words. That's an uncomfortable feeling for a writer; we make sense of the world by telling stories so when the stories stop, the world becomes a very confusing place.

This summer I found myself wondering -- as I sat wordless before my laptop -- who would write a story for the children of Eric Garner, a Black man killed on July 17 by a white NYPD officer using a chokehold. If anyone did write a story about police brutality, what press would have the courage to publish it? And what about fantasy fiction -- could it offer traumatized Black youth a temporary escape from reality, or would it only render them invisible just as fantasy novels erased me as a child? Scholar Ramón Saldívar argues that a new generation of authors can "reverse the usual course of fantasy, turning it away from... daydream, delusion, and denial" in order to "redeem, or perhaps even create, a new moral and social order."* Do such books exist for Black youth?

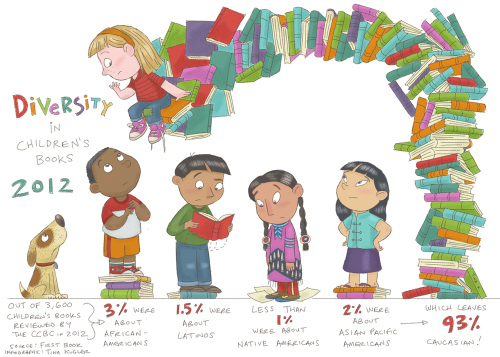

The pain and rage I felt over the August 9 police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO only heightened the frustration I feel whenever I think about inequality in the children's publishing industry. There's clearly a direct link between the misrepresentation of Black youth as inherently criminal and the justification given by those who brazenly take their lives. The publishing industry can't solve this problem, but the relative lack of children's books by and about people of color nonetheless functions as a kind of "symbolic annihilation." Despite the fact that the majority of school-age children in the US are now kids of color, the US publishing industry continues to produce books that overwhelmingly feature white children only. The message is clear: the lives of kids of color don't matter.

When artist Maya Gonzalez asked me to join her in making a statement about the crisis in Ferguson, I initially pulled back. I didn't think I could say anything encouraging or even coherent when all I felt was bitter betrayal (according to a Pew Research Center poll taken the week after the shooting, 47 percent of whites felt the issue of race in the Ferguson case was getting more attention than it deserved). Instead I dug up a decade-old picture book story I wrote about lynching and hired an artist to illustrate the book. I daydreamed about moving to London. I revisited Marita Bonner's 1925 essay "On Being Young -- a Woman -- and Colored:

You long to explode and hurt everything white; friendly; unfriendly. But you know that you cannot live with a chip on your shoulder even if you can manage a smile around your eyes -- without getting steely and brittle and losing the softness that makes you a woman.

After a week had passed, I wrote Maya back and suggested we start a video campaign that would feature members of the children's literature (kid lit) community. Lots of people clamor for greater diversity in kid lit but remain silent whenever another Black teenager is shot down -- Ramarley, Trayvon, Jordan, Renisha, and now Michael Brown. They cling to the fantasy that white supremacy has shaped every US institution except the publishing industry. They look at the reality of racial dominance in children's literature and pretend that the innocence ascribed to white children extends equally to Black children. At a moment when 75 percent of whites have no minority friends, the need for diverse children's literature (which can foster cross-cultural understanding at an early age) is greater than ever.

The Kid Lit Equality movement asks people to stand up and speak out about the ways our community serves -- or could better serve -- youth who are marginalized in our society and then under- and/or misrepresented in children's literature. Some of us are traditionally published authors and some of us have started our own presses in order to create a wider range of stories that reflect these kids' diverse realities. In the past year I have released seven books for young readers. These titles show the resilience of Black youth as they face various challenges -- divorce, bullying at school, gang violence, homelessness, the loss of a loved one. Yet they also feature a touch of magic -- a protective phoenix, a mirror that reveals one's ancestors, a boy encased in a glass bubble. Self-publishing these seven books still leaves me with 20 unpublished manuscripts and several works-in-progress. I haven't given up on traditional publishers but I don't have time to wait for them to do right by our kids. We need Kid Lit Equality now, but believing that it will come from within the publishing industry is a fantasy we just can't afford.

*Ramón Saldívar, "Historical Fantasy, Speculative Realism, and Postrace Aesthetics in Contemporary American Fiction," American Literary History, Volume 23, Number 3, Fall 2011 (574-599).