Here be dragons – and wolves, bears, witches, camels, elephants, orcs, elves and hobbits.

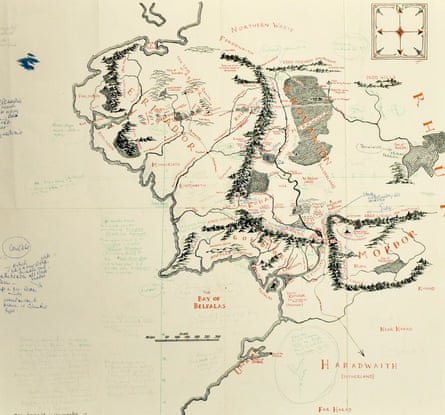

A map of Middle-earth, which to generations of fans remains the greatest fantasy world ever created, heavily annotated by JRR Tolkien, has been acquired by the Bodleian library in Oxford to add to the largest collection in the world of material relating to his work, including the manuscripts of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy.

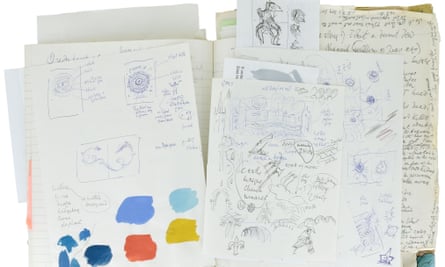

The annotations, in green ink and pencil, demonstrate how real his creation was in Tolkien’s mind: “Hobbiton is assumed to be approx at latitude of Oxford,” he wrote.

The geographical pointers were intended to give Pauline Baynes, the artist who was creating an illustrated map of his world, guidelines about the climate of key sites in the story. “Minas Tirith is about latitude of Ravenna (but is 900 miles east of Hobbiton more near Belgrade). Bottom of the map (1,400 miles) is about latitude of Jerusalem,” he advised.

“‘Elephants appear in the great battle outside Minas Tirith (as they did in Italy under Pyrrhus) but they would be in place in the blank squares of Harad – also camels.”

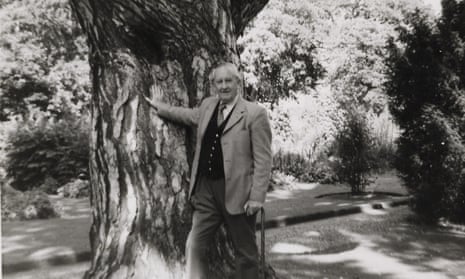

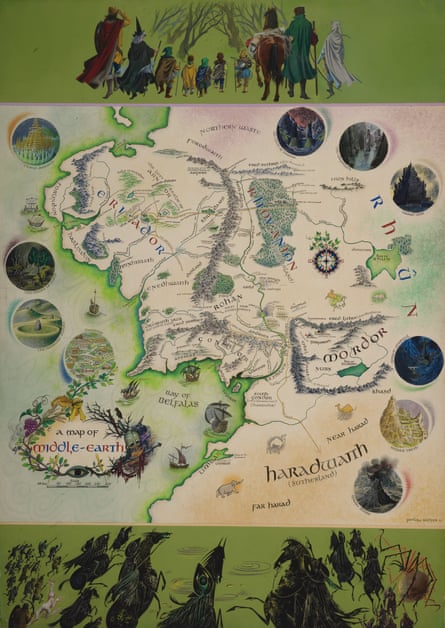

Baynes was the only illustrator Tolkien approved, and he also introduced her to his Oxford friend CS Lewis, which led to her illustrating all of his Narnia books. Tolkien and Lewis were members of The Inklings group of Oxford authors and academics. They used to meet and read from their latest work in the Eagle and Child pub, according to Oxford legend leading one disenchanted member of the circle to groan: “Oh no, not another fucking elf.”

Her poster map, published in 1970, was bordered with the first illustrations of Tolkien’s characters, but was based on the fold-out map in the first volumes of the 1954 Ring trilogy, which had been drawn by Tolkien’s son, Christopher, to his father’s meticulous instructions.

Baynes tore the map out of her own copy and took it to Tolkien, who covered it with notes, including many extra place names that do not appear in the book. Since most were in his own invented Elvish language – spoken fluently by the many devoted fans – he helpfully translated some: “Eryn Vorn [= Black Forest] a forest region of dark [pine?] trees.”

He dictated the colours of the ships and the emblems on their sails: “Elven-ships small, white or grey … Numenorean (Gondor) Ships Black and Silver … Corsairs had red sails with black star or eye.”

Baynes died in 2008, but the map was only rediscovered last year, tucked into a book she had owned. The Oxford bookshop Blackwells put it on display and valued it at £60,000. The Bodleian managed to buy it with grants from the V&A Purchase Fund and the friends of the library.

Chris Fletcher, the keeper of special collections at the Bodleian, said maps were central to Tolkien’s storytelling, and it would have been disappointing if it had gone overseas or into a private collection.

“This particular map provides a glimpse into the creative process that produced some of the first images of Middle-earth, with which so many of us are now familiar. We’re delighted to have been able to acquire this map and it’s particularly appropriate that we are keeping it in Oxford.

“Tolkien spent almost the whole of his adult life in the city and was clearly thinking about its geographical significance as he composed elements of the map. It would have been disappointing had it disappeared into a private collection or gone abroad.”