B.J. Novak Proves That Kids' Books Don't Need Pictures

The former actor and writer for The Office has found a mischievous way to entertain preschoolers through the written word alone.

Sooner or later, every parent learns a difficult lesson: There are a lot of truly boring children’s books out there. B.J. Novak’s Book With No Pictures is not one of them. There are no cloying baby animals, no peek-a-boo flaps, no educational checklists at the end—just page after page of words. Those words form statements like, “My only friend in the whole wide world is a hippo named Boo-Boo Butt.” The joke is that the grown-up has to say every outrageous thing on the page, which makes the kid feel like an evil genius.

The Book With No Pictures is Novak’s first book for children, but he is the author of a book for adults, One More Thing: Stories and Other Stories. He also spent years writing for the NBC show The Office, where he was a co-executive producer and played the role of Ryan, the temp who turned into an incompetent MBA. Novak spoke to me about comedic timing, the rebellious nature of text, and why he likes words that start with the letter b.

Jennie Rothenberg Gritz: You don’t have any kids yourself. What made you want to write a book for preschoolers?

B.J. Novak: Like many comedians and comedy writers, I really love getting a kid to laugh. It’s so validating—you know there’s no such thing as the polite laughter of a child. There’s only real laughter. You can really get hooked on that. So any time I’m at friend’s house with kids, I always selfishly ask, “Can I read your kid a book? Do you have any Dr. Seuss, any Mo Willems?”

The actor in me started to realize that there was something very funny about the whole experience. This kid was handing me a script: “Here are your lines tonight. Please perform for my enjoyment.” I thought the funniest thing in that situation would be for me to have to say things I don’t want to say—things that the kid is making me say.

So it came from there. If the adult had to say silly things, I knew the kid would feel very powerful and would feel that books are very powerful. Working backwards, I realized that if there were no pictures, it would be an even more delightful trick: The kid is taking a grown-up style book and using it against the grown-up.

Rothenberg Gritz: Some of the best children’s book writers never had kids themselves. Dr. Seuss, Maurice Sendak ...

Novak: Yeah, and H.A. Rey. I’ve noticed that, too. I hope I do have kids one of these days. But for now, maybe I’m more interested in having all kids as my audience.

Rothenberg Gritz: Maybe you also feel like you can be more irreverent than a parent might be.

Novak: That’s true! The books I loved as a child all had one thing in common: They were very fundamentally on the side of the kid. They represented mischief. That’s what really got me interested in reading. For all Dr. Seuss’s educational accolades, every kid sees what he’s doing and knows, “This guy is Team Kid. This guy isn’t trying to teach me anything. It’s a rebellious, joyous book just for me.”

Rothenberg Gritz: How much editing do you go through for a book like this? Did you have to try out lots of different nonsense sounds before you came up with phrases like boo-boo butt and ba-doongy-face?

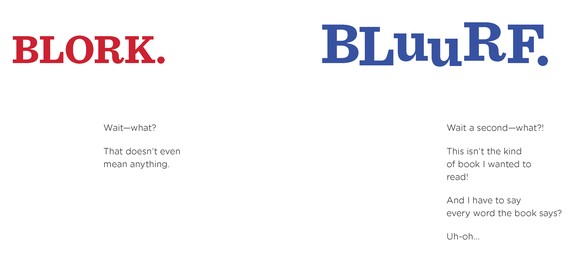

Novak: Those came pretty naturally on day one. I don’t know why, but b sounds came out as the music of the book. Boo-boo butt, blork, bluurf. There seemed to be something explosive and innocent at the same time about silly words that started with a b.

I did take a few pages out from the beginning for rhythm. Some of the early versions of the book were a little slow to start. When you have a book with no pictures, the kid is immediately intrigued. But if it’s not funny soon, the kid says, “No, I don’t think so.”

Novak: I did a million different tweaks in the design process to help give parents those cues. I put in page breaks to force a certain timing: You turn the page at the point where a comedian would pause. I also put in visual stage directions. There are small words underneath the big words that indicate the under-the-breath comment of a parent: “I didn’t want to read those words! What kind of a book is this?” It’s sort of an aside, but you say it loud enough so the kid can hear it. Everyone naturally knows that you read small print that way.

And when something is really silly, the words take on a brighter color and a much bigger size. When it says, “I am a monkey,” the words are orange. And then, when it says, “I am a robot monkey,” we chose a robotic font, which makes most people read in a robot voice.

Rothenberg Gritz: Did you test all this out before you published the book?

Novak: My father [the author and humorist William Novak] gave me great advice about stand-up comedy. He said, “You only say what you like and only keep what they like.” When I was working on this book, I made a paper-clipped version and brought it to every kid I could. I always asked the parents to read it so I could watch what they would naturally do.

Then I worked on it until I had a foolproof script: If they read it straight, it would be funny. If they read it silly, it would be funny. The real humor of the book is the way it plays on the bond between the adult and the child. If you’re an authoritative parent, it’s funny. If you’re a warm, more effusive parent, it’s funny in a different way.

Rothenberg Gritz: Your dad seems like the kind of parent who would have encouraged a rebellious approach to reading.

Novak: Absolutely. When he saw that I loved Shel Silverstein, he very carefully introduced me to Uncle Shelby’s ABZs, which is a fake children’s book written by Shel Silverstein—it’s for adults, and it’s a nightmare book to give your kids. It encourages kids to steal money from their parents and mail it to Uncle Shelby. It very much introduced me to the rebellious humor of books.

Rothenberg Gritz: What do you see as the biggest mistake children’s books tend to make?

Novak: I don’t like books that have an overt lesson to them. I think it often works against the case because kids can sniff that out. No one wants to be read an advertisement, even if the advertisement is a public service.

Reading, to me, at its most fundamental level, is freedom. Everyone who grows up loving books truly is much better off in life. The more curious you are about books, the more you self-educate. Kids start to get that in their teenage years—books can either be homework, or they can be fuel for rebellion. If it’s the latter, you love reading. This book is one way to show even the littlest kids, “This stuff is for you, buddy.”

Rothenberg Gritz: A lot of children’s authors seem to go out of their way to make their books extra sweet and gentle—the kind of thing that was ridiculed in Go the F**k to Sleep.

Novak: I love a cozy book for a kid. I just read this wonderful article in The New York Times about the hidden power of Goodnight Moon. It’s a bafflingly beautiful book. And I think The Book With No Pictures is a pretty cozy, gentle book. “I am a monkey who taught myself to read”—there are edgier things you could make a parent say. I do like rebellion. But this is controlled rebellion, not outrageous rebellion.

Rothenberg Gritz: Was it part of your goal to make kids actually look closely at the words, since there’s nothing else on the page?

Novak: It was important to me that the words look friendly and inviting. The font we chose, Sentinel, is clean but has a little bit of texture to it. I wanted the kids to think, “What is this letter? What is this word?” I stuck to simple words and tried to have them repeat often on the page: the word no, the word book. I wanted to show kids, “This is the written word, and you’re going to love it.”

Rothenberg Gritz: As the author of the first text-only book for preschoolers, what do you think about the new comic books and video games that are being designed to go with the Common Core standards?

Novak: I don’t know that the culture of text is really any better or more important than visual language. If you think about it, text is just code that we invented as societal shorthand. Now the most important thing anyone can learn is how to master this code. But there’s no fundamental reason text is superior to any other form, except that it’s been standard for so long.

That said, I am Team Text. I have an Instagram called picturesoftext. That’s truly what I love; it’s where I feel at home. And I think I can show kids what to love about text, and what is rebellious and funny about it.