Children’s picture books are a unique record of social evolution: in gender roles and racial politics, as is much discussed, but also in fashion and interior design. Children’s books deal in idealized worlds, so they’re a document of how our notion of ideal worlds has changed over time. Reading the great picture books of the past few decades is as instructive a lesson in evolving notions of design as looking at the archives of House Beautiful.

Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown; illustrated by Clement Hurd (1947)

We peer into the room—best described as eclectic—as into a proscenium, or a diorama: three walls, the central one with a fireplace, framed by windows, through which that moon is visible. Above the fireplace: a scene of a cow jumping over the moon, in an elaborate gilt frame. On the mantle below, we see a clock (the silhouette implies ormolu, but it’s bright blue in color), flanked by garniture sturdy enough to be a murder weapon out of Agatha Christie. The simple architecture of the windows is offset by green and gold striped drapery that just grazes the floor, rigged up in a way that implies volume. The clock, the frame, the curtains: It’s downright rococo.

The narrative, by Margaret Wise Brown, is modern—Modernist, really, dispensing with punctuation so that every child who grows up on it remembers her own version, the stops and starts and emphases her papa inserted into the text. Goodnight Moon was published the very year Ludwig Mies van der Rohe put a model of the Farnsworth house on display in New York, but one might assume the titular room, by Clement Hurd, is a vision of his own youth, and he was born in 1908.

The rest of the room seems to capture the spirit of the moment in which the text was written. The circular rug at the center of the room has a homespun look. The bed, the table, the lamp, the freestanding bookcase, even the andirons have clean, modern silhouettes. The toy dollhouse in the corner (perfectly symmetrical, topped with a chimney) looks like the suburban fantasy of the postwar era, or a child’s drawing. If the ceiling height and the sheer vastness of the space are upper class signifiers (I think of the Darling children’s Bloomsbury nursery), the dollhouse is a message to the sleepy middle class child: This is where you live. The fire roars companionably, and the quiet old woman stands sentry as the bunny drifts into sleep.

The Snowy Day, Whistle for Willie, and Peter’s Chair, by Ezra Jack Keats (1962, 1964, 1967)

Such is our current hunger for the retro that this family’s homes—they seem to occupy more than one, over the course of a few volumes—feel surprisingly fresh. One of Peter’s parents has a flair for pattern. The wallpaper is so alive it rises off of the page. Wallpaper these days is a creative class signifier, a mainstay of the boutique hotel, but mass-produced papers were a boon during the Depression: instant décor.

The domestic is important in so many of Keats’ books, and distinctly rendered in each. In the books about Peter, home is a sanctuary, as it is in much of children’s literature. It’s the sunny spot to which our hero returns after wandering winter streets, playing in a trash-strewn vacant lot. Peter’s home is more than that wallpaper, though that’s the most memorable flourish. There’s the handsome furniture, mostly in the Danish modern vernacular, and in Whistle, there’s the mirror, simply framed, hung on a wall abloom with yellow flowers, the black boy doubled, Peter given the gift of seeing himself. In Peter’s Chair, he is given this gift again, in the form of the framed baby portrait of himself, naked, on a fluffy rug. These objects communicate (as clearly as the be-hatted father and the pet dachshund do) that this is a middle-class home. Indeed, middle-class homes still look this way.

The heroes of Keats’ later oeuvre (Louie, Roberto, Ben and his brother Sam) inhabit a world less sunny and cheery. Theirs are homes in which parents rarely figure, are merely a voice drifting in from another room. Their walls and hallways are dark, filled with cigarette smoke and the sounds of bickering; homes you yearn to escape. But Peter’s is a home you wish to visit, one which Peter himself wants not to leave: witness his desire to sit and fit in his baby chair forever.

The House on East 88th Street and Lyle, Lyle Crocodile by Bernard Waber (1962, 1965)

The writer and illustrator Bernard Waber didn’t name his breakthrough book for its intriguing protagonist, Lyle, the New York sophisticate who happens to be a crocodile. He called it The House on East 88th Street, and why wouldn’t he—what a house!

It’s the quintessential uptown brownstone, still the beau ideal for the city’s millionaire strivers and location scouts. The house tells us all we need to know about the world of this book: that father wears a hat to work, that mother cooks and goes shopping, that an Italian impresario is the very embodiment of the foreign (there are no little boys who look like Peter on this 88th Street).

The house is grand, impossibly big for so small a family: Their first day there, after supervising the movers (please be careful with that gorgeous floral sofa, gents), Mrs. Primm ascends the sweeping staircase and stands, puzzled, before one of the many doors on the landing. That splashing sound is Lyle, of course, frolicking in the tub. Lyle comes with the house, for reasons never satisfactorily explained; he is the domestic come to life, and like the house, he’s larger than life, refined, and wonderful.

Mrs. Primm is a woman of impeccable taste. We can see, from the outset, her excitement about the house, and it’s intriguing that it’s she who discovers Lyle, because though he plays with the Primm’s son Joshua, in truth, Lyle is Mrs. Primm’s boon companion. He accompanies her as she visits the city’s antique shops and department stores, and the two skate together on the ice at Rockefeller Center. But Mrs. Primm’s sphere is the home, and so too is Lyle’s: He helps her make up the beds and fold the linens, and serves as her sous-chef.

Mrs. Primm sets a gorgeous table: footed bowl, laden with fruit, two candelabra, a bottle of seltzer, cut crystal glasses for her and the husband, covered dishes (though it seems, from the above, that she perhaps takes only a half grapefruit at mealtimes?). The chairs look slip-covered, not to modern tastes. The fixture overhead is almost certainly Louis Comfort Tiffany; Mrs. Primm is not a woman who’d buy a knockoff. The breakfront brims. The house on East 88th Street is one of beauty, and one of bounty.

Best Storybook Ever by Richard Scarry (1967)

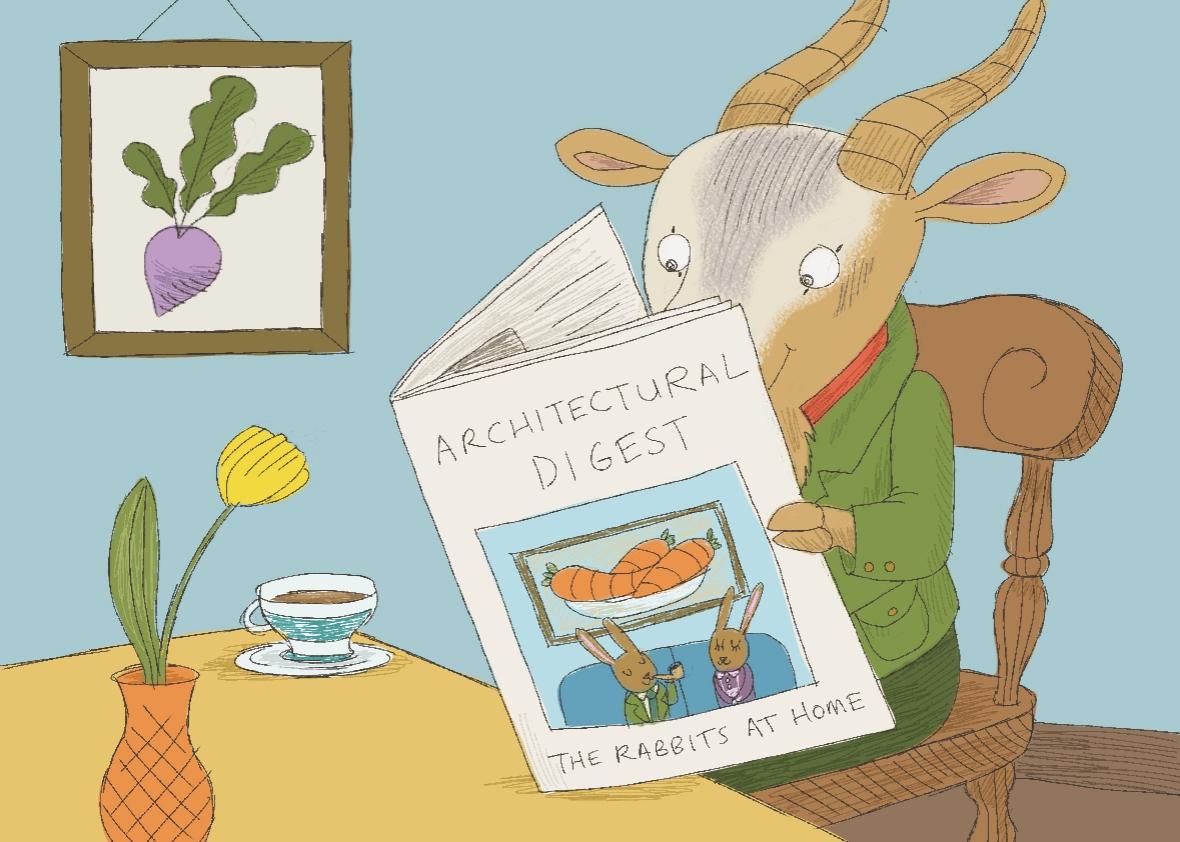

The rabbit family’s house makes me think of Cheever: green shutters and jaunty red exterior concealing a well-ordered interior, though it’s all surface, no emotion, so perhaps the Cleavers are a more appropriate touchstone. All of Scarry’s work is curiously emotionless, similarly removed—detached, just like suburban homes are said to be, in real estate parlance.

Scarry was artful enough not to have relied on literal symmetry, here—he didn’t need such a device to express his domestic ideal, one that reflects the artist’s Boston upbringing and his adult life in Switzerland. The architectural argot is clearly New England, the emphasis on order and harmony somehow Swiss.

The golden yellow of the kitchen recurs in the stairwell, hung with framed family portraits, though the family are art lovers, of a sort, given the still life above the living room sofa. (Or perhaps what they truly love are carrots.) Let’s note what seems to be a twin bed in the master bedroom and the fact that you can’t see the toilet, much as in the Brady Bunch homestead; again, literature for children isn’t about the unvarnished truth, though to be fair, you rarely spy a toilet in the pages of Elle Décor. The dining room hutch has a country vibe, something found antiquing one weekend.

The silhouettes of the sofas in the living room and the attic den are similar. This is not a home of ostentatious decorative gestures, but one of comfort, a faith in the modern culture (the television, the record player, a single book, from the Book of the Month Club, no doubt, left out on the coffee table). We see the home at the start of the day: one son lacing up his shoes, mother working on breakfast. The house is awake, alive with an optimism about what the day, the decade, the century holds for the people who live here, the people who live like this.

The Berenstain Bears series by Jan and Stan Berenstain (1962–Present)

The house is an architectural impossibility. It’s set high in a tree that’s less a tree than a giant broccoli, the rooms upstairs where the boughs and leaves ought to be, but we suspend disbelief; we already know, from Going on a Bear Hunt, that bears live in caves.

They’re known as the Berenstain Bears for their creators; their own surname is Bear, the family members known only as Papa, Mama, Sister, and Brother. (They were joined, at some point, by another sibling, called Honey.) The façade’s pink accents and mullioned windows borrow from Victorian architecture, but the house, on a dirt road in Bear Country, represents the bucolic ideal.

Papa is a carpenter by trade, clad always in blue overalls and yellow plaid shirt. While the house is largely Mama’s domain (though one of the many books in the series sees Mama enter the workforce; recent installments shown how the Bears stay safe while online), Papa’s workshop is adjacent and much of what we see in the house must be his handiwork. This is sometimes addressed in the plot—when the cubs struggle to keep their room tidy, Papa whips up a pegboard and toy box.

Other details—the cubs’ bunk beds, certain chairs, the staircase railing, the picture frames that nod to Tramp art—seem to be simply hewn wood, knotted, occasionally still abloom with a stray leaf. In a classic of the series, The Berenstain Bears and the Truth, the plot concerns the destruction of Mama’s favorite lamp, which is perched atop a roughly formed end table with the sort of rustic look that wouldn’t be out of place in one of Ralph Lauren’s Western fantasias. That prized lamp is hideous, something you’d find at a junk sale. Mama and Papa, thrifty and commonsensical, glue it back together.