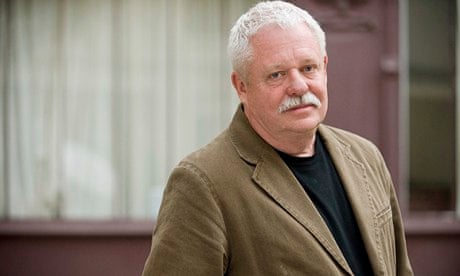

In 1974, when Armistead Maupin began writing what became Tales of the City, he thought of it as "an in-joke about the way life worked in San Francisco". Four decades later, that in-joke has been shared by more than 6 million readers. His stories of interlocking gay and straight lives in the city constitute one of the best-loved of literary sagas. The New York Times described reading them as "like dipping into an inexhaustible bag of M&Ms, with no risk of sugar overload". Now though, after four decades, that bag is finally about to be exhausted. The series will conclude with Maupin's ninth book, Days of Anne Madrigal, published at the end of this month.

Quentin Crisp once introduced him with the boast: "This is Mr Maupin. He invented San Francisco." More importantly, Maupin virtually invented the mainstreaming of gay life and helped the world see that "the gay experience" was nothing lesser or greater than human experience.

Maupin came to a realisation of his homosexuality relatively late. He was 30 when he came out, the same year he began writing. Taking stock of himself the way he would one of his characters, he once observed: "He had kept his heart (and his libido) under wraps for most of his life, only to discover that the thing he feared the most had actually become a source of great comfort and inspiration."

At the time he began writing, he saw gay fiction as both bleak and myopic. This was an era when Truman Capote still equated his homosexuality with his alcoholism and a climate in which Gore Vidal could claim: "There were homosexual acts, but not homosexual people." Maupin, however, had discovered a joyful fraternity and welcoming community in the bath houses and nightclubs of the city and decided, as he put it, to "[allow] a little air into the situation by actually placing gay people in the context of the world at large".

In doing so, he created a gloriously large world: his characters are a sprawling cast of eccentrics centred on 28 Barbary Lane, an address now firmly fixed in the canon of fictional residences. It's a household presided over by Anna Madrigal, the marijuana-growing, transgender landlady, who considers herself "a self-made woman [...] no one else in the world like her". In The Days of Anna Madrigal, we find her as a 92-year-old, living with her ersatz family of strays and planning a trip to Burning Man, the week-long hippie bacchanalia held in the desert.

It's the kind of bohemia that would have blown a young Maupin's mind. He grew up in a conservative household in North Carolina, the son of a lawyer and a housewife. He first saw San Francisco in the late 1960s as a naval officer on his way to Vietnam and was instantly smitten. (Maupin later left his mark on military history in 1970 by being the last American sailor to withdraw from Cambodia.) It wasn't until he was 27, after a brief and ill-advised stint at law school, that he became a resident, beginning the tales soon after, first in the alternative weekly the Pacific Sun before being picked up by the San Francisco Chronicle two years later.

He has said: "I conceived it by the seat of my pants, in a state of abject panic every morning." That explains the titbit-length chapters, the chatty rather than polished prose, and the glibly humorous tone.

Maupin has admitted that in the early days he kept Michael, the gay character, "very low key because I knew they'd say no if they saw what I was up to". Only once he had secured a solid following, hence a degree of control, did he feel comfortable bringing the gay characters in.

But even in San Francisco, the place where, as Edmund White put it, "gay men came from across America to learn how to live gay lives", editors were squeamish about those gay lives taking their place in print. One of his bosses at the newspaper kept a baroque chart of the Tales' dozens of characters on his office wall – an effort to ensure, as Maupin drolly noted, "that the homo characters didn't suddenly outnumber the hetero ones and thereby undermine the natural order of civilisation".

But however outlandish his characters and their adventures, Maupin's world always feels curiously wholesome. Perhaps that's because everything in the Tales has been taken directly from his own very contented life. Luckily, it's a life that seems to attract enough colour to keep the stories rollicking along with ease.

There was an affair with the Hollywood movie star Rock Hudson, for example, who was coyly "named" in the Tales with a line of blank spaces. A name effaced in print then, but later unforgettable when he became one of the first celebrities to speak publicly about having Aids. Hudson died in 1985, a year after Maupin published Babycakes, a novel widely regarded as the first work of fiction to address the crisis.

Maupin's most famous character and the most obvious authorial alter ego is the meek naif Michael "Mouse" Tolliver. It was through him, in fact, that Maupin came out to his parents. In the second book, 1980's More Tales of the City, Tolliver writes a letter to his mother and father telling them he's gay; Maupin knew that his parents, subscribers to the Chronicle, would read it. Maupin Senior went on to lovingly accept his son as a gay man while Maupin himself has gladly accepted his role as a very visible gay icon.

"I realised," he said, "that part of my function was to be very clear and very public as a gay man. I'm prouder of that than anything else I've done."

In 1989, Maupin wrote what he thought was the last of the Tales series. In the nearly two decades that followed he kept busy with a 1993 TV mini-series of the Tales and a non-Tales novel, Maybe the Moon. In 2007 though, he returned to the Tales. His seventh book went by the quietly triumphant title, Michael Tolliver Lives and sees a 55-year-old HIV positive Michael reflecting on surviving.

Critics have rolled their eyes at the Tales' many soap opera-like improbabilities, unaware that some of their furthest-fetched plot twists came from real life. In Michael Tolliver Lives, for example, our protagonist first sees his lover, Ben, on a dating website and then miraculously runs into him on the street. Maupin was browsing Daddyhunt.com when he came across Christopher Turner, an adult-film producer, but was too timid to message him. Soon after, he spotted him and chased him down Castro Street shouting the inimitable pick-up line: "Didn't I see you on Daddyhunt.com?" The couple will celebrate their seventh wedding anniversary next month.

Nonetheless, Maupin has for many years gently resisted the designation "gay writer", wary of the literary ghettoisation that it can bring. "I'm very proud," he said, "of being in the gay and lesbian section, but I don't want to be told that I can't sit up in the front of the book store with the straight, white writers."

Ian McKellen is a friend and fan and it was to Maupin that he turned in 1988 when he agonised about coming out. Maupin urged him out of the closet, telling him he'd be a happier man and a stronger artist for it.

Maupin's work is just as loved by younger generations. Jake Shears, frontman of Scissor Sisters, was given the books as a 13-year-old by a couple of older gay friends and has described them as "a rite of passage". Like so many, he went on to read the entire series, meaning that when he was asked to work on a musical adaptation he said yes on the spot. The musical premiered in 2011 in – where else? – San Francisco.

Maupin is 69 now. Two years ago, "craving a little more space and some nature", he left his beloved San Francisco for Sante Fe where he and Turner live with their labradoodle. Nonetheless, the city he chronicled for all these decades continues to love him back; 12 June (the publication date of Michael Tolliver Lives) will always be, as mayorally decreed, Michael Tolliver Day and tour guides still conduct walking tours of Maupin's city.

Harvey Milk, the first openly gay US politician, was assassinated two years after Maupin began the Tales and in the four decades since Maupin has seen the world change. There's the internet, which he's taken to happily (his tweets are dotted with smiley faces and "darlings"), but, more importantly, he's witnessed huge victories for gay rights .

It's a testament of sorts to the belief that's guided Maupin all along, namely: "The world changes in direct proportion to the number of people willing to be honest about their lives."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion