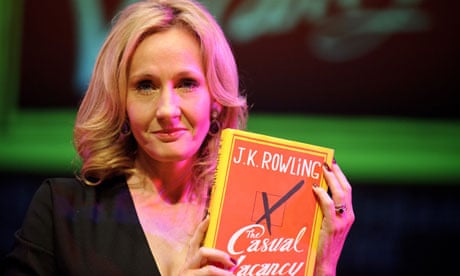

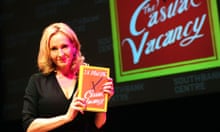

Dark, devious and devilish, JK Rowling's first post-Potter novel, The Casual Vacancy, reads like an episode of Postman Pat written by the makers of The League of Gentlemen. The fictional village of Pagford is a contemporary Cranford, sizzling with the malice of small minds.

Yet critics have been just as foul-mouthed as Rowling's meanest characters. Some have described the way it swings from openly abusive relationships and grinding poverty to the easy suburban comedy of golf clubs and local scheming as cartoonish and unsubtle. The Daily Mail thought it was "a socialist manifesto, masquerading as literature", while the Sunday Times questioned why Rowling "seems so down on middle-class values".

Rowling's books, including Potter, certainly reflect the claustrophobia of identikit suburbia, whether it be (fictional) Little Whingeing, where Harry grew up, or (real) Chipping Sodbury, where she spent time herself. But what bites most keenly is the hypocrisy of those places, something she is uniquely placed to understand and convey: as she commented in her Front Row interview with Mark Lawson last week, she has had experience of living at almost every point on the social scale, from lower middle-class suburban boredom to "being as poor as you can be without being homeless" to extreme wealth. When poor, she was treated as invisible; with increasing wealth has come an outer perception of increasing respectability.

She knows – and shows in her fiction – that outward respectability and social approval do not automatically mean moral goodness. Vernon Dursley, Harry Potter's uncle, is a middle-class bore, social climber, hothead and snob. He is (like Simon Price in The Casual Vacancy) an abusive man who represents himself as a decent chap. There are millions of Vernons and Simons out there: they are the ones who bully their wives and children, who read the Daily Mail, who think that poor British people are lazy, that migrants are coming over to fiddle the benefits system, and that, if everyone bucked up, the country wouldn't be in such a mess.

The Casual Vacancy is not about the cosmopolitan middle classes, with their dreadful children called Oscar and Milo and Noah (or, as I heard a woman telling a new friend at the theatre the other night, Blue and Day). The Pagford set have achingly banal names, satellite town names: Colin, Tessa, Patricia, Miles, Samantha. They are middle-class, middle-brow, with middling IQs. They express their existential pain through rage and judgment. "Mugglemarch", the handle that the book has gained, strikes me as not pejorative and not incorrect. We are in the world of the Trollopes, Agatha Christie, Elizabeth Gaskell, Barbara Pym and Jane Austen, where archetypes reveal truths.

The novel has been accused by the Telegraph of being at its weakest when it is "angrily political" – meaning that Rowling dares to criticise the class divisions in society and examine the injustice, inequality, hypocrisy and prejudice which keep them in place. The criticism is the bleat of people who think of themselves as neutral, apolitical and commonsense but are fiercely political in defence of their own privilege. The same people who happily swallow the extreme snobbery of Downton Abbey or laugh at those they label "chavs" and "hoodies" get angry when the arrow hits closer to home.

But that is exactly what the "nice" people of the suburbs and middle England can be like. There was the close school friend who said one day: "Last night at dinner my dad stood up and said the Asians were taking over the country and then my mum stood up and agreed with him." There was the mother of a classmate who, one night during a school play, turned to my mother and hissed: "If you came any closer, you'd be sitting on my lap." Later, when I'd gone to their house to play violin, she greeted my mother with the words, "Yes, I heard them screeching away up there." There were the women I witnessed at the charity shop haranguing a British Chinese woman who had made a mistake about a price, drove her out in embarrassment, turned to each other with smug little mincing smiles of satisfaction and simpered, "I don't think she's from around here."

The strikingly Pagfordian, outraged reaction of some critics demonstrates how accurate the novel is in its critique of the class from which they all come. Rowling is the only middle-class novelist to peer behind the John Lewis curtains at the bigoted and nasty behaviour going on in the "lounges" of her peers, concealed by a veneer of social nicety. It is not middle-class values she is attacking but middle-class hypocrisy. Petty smearing, snide undermining, toxic insinuation, the desire to belittle and sabotage a gifted woman, subtle demeaning: these traits are common in many people, from small-town saboteurs to national book critics.