Robert McCrum: ‘His late prose has the command, rhythm and simplicity of greatness’

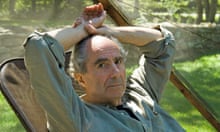

When I interviewed Philip Roth in 2008, the year of his 75th birthday, at his pastoral home in upstate Connecticut, there seemed to be mainly three things on his mind: outliving his contemporaries and rivals; the ongoing fuss about the Nobel committee (would they/wouldn’t they?) and Portnoy’s Complaint.

As Roth, who died last week, at the age of 85 – just a few days after another master of American prose, Tom Wolfe – glides into the literary pantheon, those first two worries have become irrelevant or trivial, but that frustration with the legacy of Portnoy was prescient. This “shocking” novel is now more than 60 years old, but some readers still haven’t got over his brilliant, comic exploration of a young man’s frustrated sex drive, especially as it might relate to an Jewish-American boy’s mother. A novel in the guise of a confession, it was taken by many American readers as a confession in the guise of a novel: Portnoy became an immediate bestseller and a succès fou.

Let us not forget, in honouring Roth’s exit, that to facilitate his solitary passion, Portnoy commands a far richer arsenal of sex aids than most horny young men: old socks, his sister’s underwear, a baseball glove and – notoriously – a slice of liver for the Portnoy family dinner. This is the “talking cure” Freud never envisaged, a manic monologue, to quote its author, by “a lust-ridden, mother-addicted, young Jewish bachelor”, a farcical tirade that would put “the id back in yid”. Perhaps only Harold Pinter, to whom, as a young man, Roth bore some resemblance, could have framed such a memorable and outrageous line.

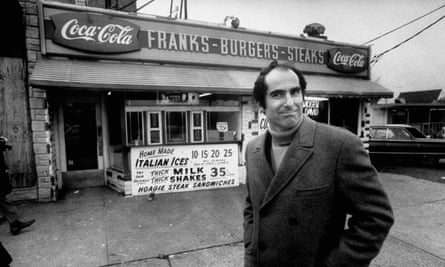

Philip Milton Roth was born into a family of second-generation American Jews from Newark, New Jersey, “before pantyhose and frozen food”, he liked to say, in 1933. His parents were devoted to their son. “To be at all,” he writes of his mother and father in his autobiography, “is to be her Philip [and] my history still takes its spin from beginning as his Roth.”

He came of age in Eisenhower’s America, growing up in the suburbs, across the Hudson, temporarily separated from the glittering temptations of Manhattan, but part of a generation of young Americans, also including William Styron, John Updike and Saul Bellow, who wanted to re-examine and renew their society in the aftermath of the second world war, the Holocaust and Hiroshima. Roth’s seniors – Norman Mailer, Gore Vidal and Kurt Vonnegut – had already shown the way in their feisty takeover of the American novel. Roth, too, would set about this task through his books, bursting on to the surprisingly genteel American literary scene with Goodbye, Columbus in 1959.

From his precocious beginnings, Roth learned to endure the kind of attention that might have led even the most dedicated headline-hog into distracted solipsism: a persistent grumble of low-grade hostility, the envious scrutiny of literary minnows and, after Portnoy’s Complaint was published in 1969, incessant jokes about “whacking off”. How quaint his literary misdemeanours seem today. From many points of view, Roth’s career epitomised the humorist Peter de Vries’s observation about American letters that “one dreams of the goddess Fame – and winds up with the bitch Publicity”.

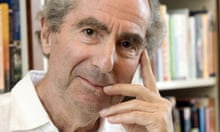

Some critics still berate him for his insouciance towards convention, and his assaults on the American dream. Had he, I wondered, when we met, ever unconsciously courted outrage ? “I don’t have any sense of audience,” he replied, “least of all when I’m writing. The audience I’m writing for is me, and I’m so busy trying to figure the damn thing out, and having so much trouble, that the last thing I think of is: ‘What is X, Y, or Z going to be thinking of it?’” There, in a sentence, is the authentic Roth: neurotic, obsessive, disdainful and self-centred. The only thing that’s missing is the outrageous humour (mimicry, fantasy, satires and riffs) that accompanied any conversation with the writer when he was in the mood, and on a roll.

The savage indignation mixed with self-hating rage that characterised the young Roth pitched him, as a young man, into a world of banal public curiosity. He would spend most of his mature life fleeing its Furies, insisting that his fiction was not autobiographical. But anyway: so what ? The themes of his early work were the constant themes of his work as a whole: the sexual identity of the Jewish-American male and the troubling complexities of any relationship with the opposite sex.

Those critics who, on his death, have complained about Roth’s “narcissism” and associated transgressions, are missing the point. Such remorseless self-examination – from Tristram Shandy and Huckleberry Finn to Tender Is the Night and The Naked and the Dead – is the novel’s timeless business. For Roth, Portnoy set the template for all his work, the exquisite torture of literary self-contemplation. “No modern writer,” Martin Amis once observed, “has taken self-examination so far and so literally.”

After Portnoy, Roth took refuge from celebrity in his alter ego, Nathan Zuckerman, and from the pressures of American literary life in long spells of travelling across Europe and England, culminating in his marriage to the actress Claire Bloom. This middle period of his fiction, dominated by the Zuckerman novels, and his second marriage (his first wife had died in a car crash in 1968) became increasingly troubled by his quest for artistic fulfilment.

The Zuckerman books, for example, The Anatomy Lesson and The Counterlife, delighted and exasperated Roth’s critics and fans. “Lives into stories, stories into lives,” observed the literary critic and biographer Hermione Lee, “that’s the name of Roth’s double game.” The novelist himself hated to be asked about his alter egos. “Am I Roth or Zuckerman?” he would gripe. “It’s all me. Nothing is me.” Or, in Deception: “I write fiction and I’m told it’s autobiography; I write autobiography and I’m told it’s fiction. So since I’m so dim and they’re so smart, let them decide what it is or isn’t.”

As much as the wild humour of a writer given to memorable comic effusions, this prickliness was typical. His self-assured belief in his profound originality first animated and then poisoned his relationship with Bloom who, having declared that she wanted “to spend my life with this remarkable man”, divorced him in 1995, after years of provocation. Roth had put his adultery into fictions such as Deception (1990), a ruthlessly exact account of an American husband’s escape from a jealous wife in his affair with a cultivated English woman. Bloom got her revenge in 1996 in Leaving a Doll’s House.

After the break with Bloom, Roth retreated into splendid isolation in Connecticut, working day and night, a lonely and rather tetchy old man with a notoriously short fuse. He celebrated this life in his 1979 novel The Ghost Writer: “Purity. Serenity. Simplicity. Seclusion. All one’s concentration and flamboyance and originality reserved for the gruelling, exalted, transcendent calling… this is how I will live.” Sequestered with his muse, artistically he was free. As if to confound F Scott Fitzgerald’s celebrated maxim that “there are no second acts in American lives”, he hurled himself into a frenzy of composition. “If I get up at five and I can’t sleep and I want to work,” he told the New Yorker, “I go out and I go to work.”

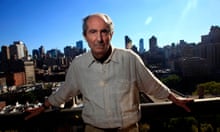

The novels of Roth’s old age still leave many American writers half his age in his dust. The turning of the 20th century saw the extraordinary late flowering of his imagination in American Pastoral (1997), I Married a Communist (1998), The Human Stain (2000), and a spookily prophetic The Plot Against America (2004). Now, at last, he was no longer an enfant terrible, but America’s elder statesman of letters. His late prose has the command, rhythm and simplicity of greatness: words written and rewritten in almost monkish seclusion.

In his final years, he lived alone, at least up there. In New York, where he wintered, as a literary lion, it was a different story. On my visit to his rural paradise, once the business of the interview was over, he showed off the pool in which he loved to swim, his lawns and, finally, the simple wooden office in which he would write, standing up, as if on guard at the gates of the American imagination. Never a day passed when he did not stare at those three hateful words: qwertyuiop, asdfghjkl and zxcvbnm. As he once said, rather grimly: “So I work, I’m on call. I’m like a doctor and it’s an emergency room. And I’m the emergency.”

Roth’s late novels were really novellas, but they still commanded, and received, respectful attention, at least from those who were not troubled by the hoary old accusations of “misogyny” and “narcissism”. Perhaps Roth sensed his end was near. With surprising humility, he liked to quote the valedictory words of the great boxer, Joe Louis: “I did the best I could with what I had.”

In 2007, he published Exit Ghost, his farewell to Zuckerman, and then, in 2010, a goodbye to all books, his last novel, Nemesis. In 2012, he told the BBC that he would write no more and ease himself “ever deeper daily into the redoubtable Valley of the Shadow”. Recognising his stature on the American scene, the Observer praised “the sheer delight of his style – that sustained, lucid, precise and subtly cadenced prose that can keep you inside the dynamic thoughts of one of his characters for as many pages as he wants”. In a way, that’s beside the point. His subject remained, to the end, in the words of Martin Amis, “himself, himself, himself”.

Robert McCrum is a former Observer literary editor. His most recent book is Every Third Thought (Picador)

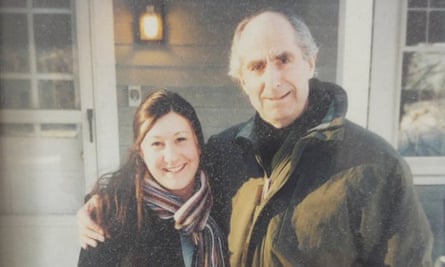

Hannah Beckerman: ‘He threw questions back at you, made you fight your corner’

It was a Wednesday afternoon when my telephone rang at work.

“Can I speak to Hannah Beckerman?” an American voice asked. “It’s Philip Roth.”

It was 2002, and I was a 27-year-old BBC television producer. A few weeks previously, I’d sent a letter to Roth’s agent in New York, pitching the idea for a documentary to mark his 70th birthday. In those days I sent a lot of speculative letters to authors I admired and rarely got a reply, let alone a personal phone call.

“So, shall we talk about this film you want to make?”

Over the next hour, Roth and I talked about his work: about accusations of misogyny (“I’m not a misogynist. I’ve never understood people saying that”); about parent-child relationships in American Pastoral; about whether Mickey Sabbath was an unlikable character. “He’s angry, but don’t you think he has good reason to be angry?” Roth did that a lot: threw the question back at you, made you fight your corner, forced you to interrogate your own position.

At the end of the call, Roth said we should “speak again”. Over the course of the next year, about once a week my phone would ring and a voice would say: “Hannah, it’s Philip.” We talked about his work, American literature, my Jewish grandfather, politics. Strangely, at the time, those calls didn’t strike me as extraordinary. I kept no journal of them, as I might do now. Perhaps it was the folly of youth, or perhaps it was because those conversations were, above all else, fun. Even when he was challenging me – and I was aware of being kept on my toes – his incisive humour broke through.

A year later, Roth agreed to take part in the documentary. It was only then that I realised he’d been vetting me: he wanted to know that I understood his work, that I appreciated it, that I was going to treat him – and his novels – with integrity.

It was a snowy February afternoon when I arrived in Connecticut with two BBC colleagues. We met Roth for dinner at a restaurant. He was funny and sharp, just as he’d been during our phone calls. We shared a dessert: something with chocolate. A friend of his arrived and joined us for drinks. Only later did I discover it was the film director Miloš Forman.

The next morning, we arrived at his home: a large, grey clapboard house nestled in the woods on a road you probably wouldn’t find if you weren’t looking for it. Roth answered the door in tracksuit bottoms and an old sweatshirt. “I’m doing my exercises. Come on in.” The sitting room was light and airy, with large windows that let in the low winter sun, and there was music playing. We chatted while he exercised on a mat laid out on the polished wooden floor. The house was lived in: bookshelves, two couches facing one another in the middle of the room, an ancient TV. I showed him how to work his misbehaving VHS machine, and he talked me through the pictures stuck to his fridge: vintage photographs, postcards of Jackson Pollock paintings (he was a fan of Pollock, not so much Rothko). He pointed out the pond in the garden where he swam and showed me his writing studio – just a few steps from the house and made from the same grey clapboard – complete with the lectern where he now wrote standing up to accommodate his bad back.

In the three days I spent filming with him, Roth was easygoing, good company – far removed from the angry, misanthropic characters in some of his novels, personality traits so many critics have wrongly attributed to Roth himself.

A couple of months later, my mobile phone rang. It was Roth to tell me he’d seen the documentary and loved it. “But who the hell was that actor you got to do the readings from my novels? His voice was all wrong.” Roth was right: the actor had been badly cast. And that final phone call from Roth sums him up perfectly: generous but challenging, raising a wry smile while highlighting errors, and with an insatiable vigour to question everything around him.

Hannah Beckerman is a novelist, journalist and producer of the BBC documentary Philip Roth’s America

David Hare: ‘American passion for newness was the source of his inspiration’

I first met Philip Roth through a mutual friendship with his fellow novelist Julian Mitchell. They had been students together in the United States. But it was when he was living in England in the early 1980s that we grew closer.

His first reason for being in London was that he was with Claire Bloom. But the move also suited his purposes. Even a writer of his steely resolve was exhausted by all the hysteria attendant on the publication of Portnoy’s Complaint. You could tell how relieved he was to be living in one of the leafier parts of South Kensington and to be working daily in a quiet room in Notting Hill.

Philip was pure writer through and through, and he was deeply interested in, and extremely generous towards, anyone who he thought took writing as seriously as he did. In particular, he showed a humorous interest in younger colleagues like me, Christopher Hampton and Ian McEwan. He liked the fact that Christopher and I worked in the theatre, because Philip clearly had an itch for the stage, which he didn’t know how to scratch. (He did eventually adapt The Cherry Orchard for Claire to play Madame Ranyevskaya in Chichester).

We took to having lunch together every couple of weeks in a chic restaurant called Monsieur Thompson’s. Philip was the wittiest conversationalist you could imagine, and it didn’t take long to notice that all his gaiety and bubbling brilliance were directed towards exposing hypocrisy. He just hated people posing as better than they were. He revelled in the play Pravda, which Howard Brenton and I wrote about a Murdoch-like newspaper proprietor, and equally in Anthony Hopkins’s demonic performance, because he said it was a sign that I was finally facing up to the fact that I wasn’t, in his words, “a nice boy”. In life, I could pretend to be nice if I wanted, that was my business, but it was a useless position from which to write. Men and women were good and evil, devious and kind, fine and flawed. You could only write well if you stopped pretending to be virtuous.

There were times when talking to him, say, about his first wife, that I began to wonder whether he was overly in love with a writer’s necessary ruthlessness. Because I once happened to be in New York, he asked me to stand in on his behalf opening the wing of a library in his old college at Bucknell in Pennsylvania. When I returned, he was desperate to hear everything about the occasion, as though there were more fictional juice for him in things being seen through my borrowed eyes rather through his own. There was a voyeuristic sparkle when I told him which of his old classmates had been there, what were they wearing, and how they had reacted to the speech he had given me to read.

In time, Monsieur Thompson’s folded, and he took instead to lunching in Spudulike. Suddenly, there was America’s most famous novelist, unrecognised, daily eating a baked potato and coleslaw, right next to Notting Hill tube. It was in Spudulike that he kept trying to persuade me to go to the Middle East. He thought the fanatical Jewish settlers were hilarious. When I protested that religious zealotry was his subject matter, not mine, he replied: “I promise you, David, these people are so crazy there’s room enough for all of us.”

By the time he left the UK, there were aspects of his behaviour – in relation to his romantic life with Claire, and to violent ruptures with one or two of his best friends – that had a new and frightening ferocity. He claimed to be driven away by upper-class antisemitism. But in fact it turned out he needed to get back home for a simpler reason. American passion for newness was the source of his inspiration.

He followed up his exile with the most astonishing run of any contemporary novelist: Sabbath’s Theater, American Pastoral and The Human Stain. In rural Connecticut he paid the local paper shop 25 cents extra to deliver his New York Times with the culture section ripped out, because it enraged him so much. Critics who had once accused him of obscenity now changed the charge to misogyny. But they were missing the point. We were entering a pious era in which, in public, people were going to claim to be without stain, working as hard on their impeccable ethical positions as they did on their abs and their pecs. But Philip, in our lifetime, was the supreme anatomist of the difference between who we claim to be and how we behave. That is why his work, more than anyone else’s, remains still loved, still resented.

David Hare is an English playwright and screenwriter. His new play, I’m Not Running, opens at the National Theatre in the autumn

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion