When I gave my father the pile of pages that would become my novel This Time Tomorrow, he quickly thumbed to the back and asked, “What page do I die on?” This was a joke and also not a joke. In the book, he (“he” being Leonard Stern, the fictional father in my novel) dies on page 301. In real life, off the page, my father, Peter Straub, died on September 4, 2022. In the book, Leonard dies in his bedroom at home with his daughter, her stepmother, and his nurse. In real life, my father died in the windowless ICU hospital room he’d been stuck in for a month, most of that time doing fairly well, recovering from a fractured hip and sitting up, reading books and watching MSNBC, just as he would have at home. My mother and brother and I were by his side, and I held his hand. It started very slowly — what page do we begin to die on, any of us — and, mercifully, ended fast.

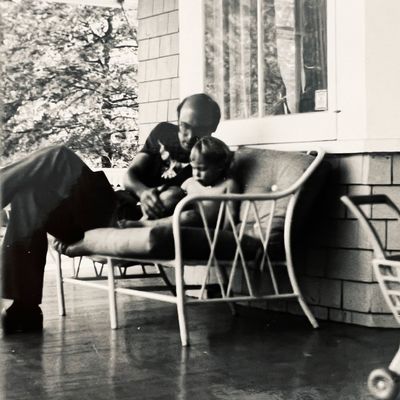

The day before he fell and broke his hip, I went over to my parents’ apartment to spend a little time in advance of leaving town for a week’s vacation. My father and I took a slow walk around the floor of his building, a behemoth of a place in Brooklyn Heights that used to belong to the Jehovah’s Witnesses, as many in the neighborhood did. Before I left, I gave him a few pages of an essay — an earlier version of this essay, in fact — I’d been writing about his 1984 novel, The Talisman, which he wrote with his friend Stephen King. I’d just finished watching the latest season of Stranger Things, and having found it more affecting than anticipated, I wrote 1,500 words in a blur. We sat at the table, and I watched him read. He laughed so hard he doubled over — I will tell you at which point — and when he was done, he said something along the lines of, “Well, that’s lovely, Emma.” That was his reaction to everything I did. Pride and amusement in equal measure.

This summer, a bookish friend posted a still of Lucas (one of the kids on Stranger Things, who had been a reedy pip-squeak in the earlier seasons and is now a handsome teenager) holding a copy of The Talisman. I had just started watching the fourth season of the show, and it seemed like a cute Easter egg — the Duffer brothers, the creators of Stranger Things, had recently been announced as the latest in a very, very long line of directors attached to a Talisman film adaptation, the rights to which Steven Spielberg had bought for a million dollars when the book was published.

My father had stories about meeting Spielberg. He and Steve (King — too confusing to have two people named Steve in this story) went to Los Angeles to meet with Spielberg, who sent a limo to pick them up. It sounds to me that my father, high on success but also probably cocaine, was being a bit of a snob about the whole thing, wanting to be wined and dined but also thinking himself very much above the Hollywood scene. After the meeting, Spielberg gave my father (and presumably Steve) a signed ET poster, which then sat in my parents’ basement for the next three decades, at which point it vanished. Spielberg’s inscription said, “Peter, your imagination is a gift to be envied.” The price that I would pay for this item, an object I saw every time I went into my parents’ basement for the first 35 years of my life, is also a million dollars. They were not given a limo ride back, which my father complained about, and I love to imagine these two hulking weirdos sitting on a curb somewhere in Beverly Hills, each clutching a poster of a bug-eyed monster in a bicycle basket, trying to figure out how to call a cab back to their hotel.

(This is where my father doubled over laughing. Yes, he said, that’s probably how it went — all the fact-checking I needed.)

When my father was in the hospital with a failing heart in the summer and fall of 2020, I decided to listen to the audiobook of The Talisman. I’d read the book when I was a tween, decades earlier, and I wanted him in my ears. (To be clear: It was the voice of the narrator, Frank Muller, I was literally listening to. He did a far better job than my father would have, a fact my father understood and respected.) Unlike most of my father’s books, The Talisman is an adventure story, and though there are deaths and a heaping dose of peril, the danger is not what I find scariest. There are no murderous pedophiles; there are no rapists. The scariest thing in the book is the fear of the main character, a young boy, losing his mother. It was what I was afraid of, too. The book kept me company as I traveled back and forth between my house and the hospital, a 45-minute trip I took once a week for four months, the only time I was apart from my own small children during that period of the pandemic. It was both an escape into my father’s voice and an escape out of my daily reality. There was less fear in the book than in my life, and even better, it had a resolution.

On my recent book tour, I had a line that killed: It was about the pleasure I get from finding my father in his books, in the paragraphs about jazz or various Milwaukee relics or the smell of a particular chocolate chip cookie, and the idea of my children someday finding little kernels of me in my books and finding a version of both of us in This Time Tomorrow. They’ll find me, and their Pops, together. Sometimes, this would make me cry. Sometimes, it would make other people cry. I said it every night and meant it every time.

The book was born from the visits with my father. The protagonist, Alice, is visiting her father, Leonard, in the hospital. He is a science-fiction writer famous for a 1980s time-travel novel that got turned into a long-running television series. The characters are not me and my father except when they are. They live on 95th Street. Our house, the one with the basement and the ET poster, was on 85th Street. Those are different zip codes. None of the facts are real, but the feelings all are.

One of my father’s friends, a handsome television actor, told my father he’d read my dad’s books to his mother when she was dying in the hospital. I’ve now had people tell me this, too, that they’d read my books either to their loved ones or beside their loved ones. We live in a time of death, rampant as wildflowers, though of course it’s always been true that people — the ones sitting in the uncomfortable chairs and the ones largely motionless in the adjustable hospital beds, lips parched, skin dry — need stories to take them somewhere else. When my mother, my brother, and I left the hospital yesterday, I had in my bag the stack of books my father had been reading—Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer, a biography of Jean Rhys, and a galley of the new Julian Barnes novel that I’d brought him from my bookstore. My mother brought home the books she had bought him for their 56th wedding anniversary eight days prior: A Taste for Poison: Eleven Deadly Molecules and the Killers Who Used Them and Hell’s Half-Acre: The Untold Story of the Benders, a Serial Killer Family on the American Frontier. Now that’s romance. Find me someone who had more books in an ICU, ever, and I will give you a large prize.

When I was doing the press for This Time Tomorrow, an interviewer said — clearly thinking they were doing me a favor — “I won’t ask any questions about your dad or your children.” It does happen a lot to writers in my particular position. It’s what I wanted so much when I was starting out, to be taken seriously on my own, but now I find I no longer care. To use the parlance of the day, what is a nepo baby at 42? He did help get me my first agent, a smart, funny woman my age who — go figure — could not find a publisher for my messy, terrible first-attempt novel that was a modernized Wuthering Heights with a smattering of Flowers in the Attic, which was very much not her fault. I didn’t publish a novel for another ten years.

Now, many of my readers don’t know who my father is, which is why I want to talk about my father. What does it mean to have a parent (and to be a parent) whose stories exist in the world? What does it feel like to be able to download an audiobook to spend more time with an earlier version of him? I just saved all of his voice-mails, one of which said, in total, “This is the hunchback in apartment nine. You’re making too much noise upstairs.”

The scene in which Lucas reads The Talisman is not a throwaway sight gag, as I’d first assumed. It’s in the final scene of the season, so brief spoilers ahead. Because I’d seen the photo, I’d been waiting for it, looking for it all season, assuming I’d missed it when walking one of my children back to their bed or opening the oven to check on dinner. I hadn’t missed it. Lucas is reading the book aloud to Max in her hospital bed. She is alive but comatose, her body broken, and he loves her. I burst into tears. I don’t know if these Duffer boys will really make the book into a movie or a television show, but I do know they get it. If anyone stole that movie poster from the basement, my money’s on them. I cried for the last 30 minutes of Stranger Things. The last hour. I’d been in it all along for Steve Harrington, the heartthrob with the incredible hair. (I married my husband for his hair.) But I wasn’t watching for Steve anymore — I was watching for the reunions between the parents and their children, knowing we each have only so many, whether we’re battling monsters from hell or only the human body’s delicate systems. Is there really such a difference?

In the hospital, I read my father two of my favorite poems — Frank O’Hara’s “Having a Coke With You,” which a friend read at my wedding, and Richard Wilbur’s “The Writer,” which is about the poet’s young daughter, also a writer. In it, the poet and his daughter help to free a bird that has flown into the house, and eventually it does find an open window, “clearing the sill of the world.” I knew the poem because my father had chosen it for my eighth-grade yearbook quote. Yesterday, all these years later, I chose the poem for him. In it, I hear the familiar clack of his fingers on the keyboard, the pauses, and the noisy return. I was both the girl and the writer, and my father was, too. He was in the room when I was born, and I was in the room when he died. How many of us make it to that room knowing that our love has been communicated, received, and reciprocated? We played his favorite music — Rosemary Clooney, Paul Desmond, Miles Davis — all of us working together to open the window and let him fly out, clearing the sill of the world.